I INTERVIEW MYSELF ABOUT MY NEW BOOK, THE END OF THE CLOCKWORK UNIVERSE:

Q: I’m so happy to spend this time with you, Fleda, to talk about your new book! I’m a great fan. I’ve read every word you’ve written. First, I want to say how much I admire the cover. Where did you get that design?

A: Great to talk with you, Fleda. To answer your question, I knew I wanted something that felt like things were flying apart. I looked at a lot of images online, especially Open Access sites. Connie Amoroso at Carnegie Mellon University Press and I tried so many different possibilities! And placing a title over the image was a problem. I found this painting from an online gallery, loved it instantly and wrote to the artist, Hyunah Kim, who agreed to let me use it for a reasonable fee. Then the problem was that the painting is square and the book is rectangular! So Connie came up with a way to separate the title from the painting and blend it all on the page. She’s a genius.

Q: How did you choose the title?

A: It’s what the physicist Nels Bohr said to fellow physicist Werner Von Heisenberg one day. What he meant is that, after what we know now—including quantum mechanics, chaos theory, and relativity—we can no longer see the universe the way Isaac Newton did. Things don’t work like a clock. Things are not determined or predictable. This is a huge shift in how we see the world! You can’t pin anything down. You can’t know anything for sure. The universe turns out to be dynamic and evolving, not static and mechanistic. Even our brains evolve depending on what’s happening with us!

Q: So, how does that relate to your poems in this book?

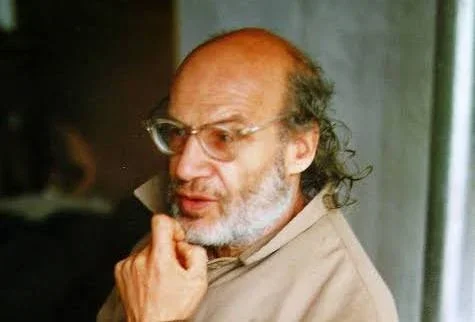

Alexander Grothendieck, maybe the world’s most brilliant mathematician.

A: The title of the longest poem in my book, “Ever-Fixéd Mark,” comes from Shakespeare’s sonnet 116. There’s a book by Chilean writer Benjamin LaBatut called When We Cease to Understand the World; I soaked it up like a sponge. The longest essay in the book is about the French mathematician Alexander Grothendieck. I especially sponged that one up. I think I wrote my poem in my head as I was reading. It is a mind-blowing story.

Grothendieck climbed down the dark hole of knowledge until he saw we really can know nothing, nothing at all. Well, he may have gone a little nuts, but what he saw was really beyond understanding.

This essay really pulled the collection together for me.

Q: But your poems aren’t esoteric. They don’t drag me down a black hole. You have poems about your mother and brother’s graves, about paper dolls, catalytic converters, a pig, a snapping turtle, and so on.

A: Still, it feels to me like every poem in this book somehow radiates the radical knowledge that nothing is fixed, nothing can be certain. You can feel that, at least I think you can.

Q: So do you think this book is different from your others?

A: That’s really for the reader to say, isn’t it? I’m different, I understand the world differently, so the poems—if I’ve grown and changed—are different. Not in a dramatic way, but they seem more open-ended, maybe.

Q: You have a series of ten “Walk” poems placed throughout the book. That’s a lot. What prompted those poems? And then, too, I want to ask how you saw them fitting the tone of the book.

A: Well—you know, Fleda—sometimes you don’t know what to do next, as a writer. Sometimes you get, not stuck exactly, but hungry for a subject. At the time I was taking regular walks, which I sincerely hope I can return to after my back/spine problem is “fixed.” But that’s beside the point. The point is, I walked in a different direction from our place every day. I observed, which is what poets do, of course. And I talked to myself (You know what that’s like). They’re very close to the surface, meaning I am telling you what I’m thinking, literally step by step. The first one introduces this theme: our stories bounce back at us like a mirror, while the trees or whatever go on being themselves. Our thoughts—our stories—are like a breeze, leaving no trace.

Q: I wonder if the post-Newton view of the world feels nihilistic? Are our thoughts merely blown away in the breeze?

A: No, not at all. A nihilist feels that life has no inherent meaning, value, or purpose. When I was a child, I understood as a child. (Remember your Sunday School lessons). I understood there was a person-like being in the sky, and that the meaning of life was to please Him. When I was a man, the scripture goes, I put away childish things. It is not necessary to carry that simple framework all your life. You see there is value in each moment of an aware life.

Poems, if they see clearly, celebrate the moments.

Q: What comes next, for you?

A: Amazingly, I have another book in the works. When we moved into a senior living residence, I kept a diary for the first six months about what that was like for me. Fastest book I’ve ever written. But I’m excited about it. It will be out in the spring.

Q: Thanks so much, Fleda, for taking time, to talk with me.

A: You’re most welcome. I always enjoy talking with you. Let’s have coffee when we have time to get together.

The P.S. . . .

It’s officially released! Order here.

Oct. 4 at 4:00, TODAY! I’ll be reading at Leeland Library, the Old Art Building

Oct 19 at 4:00 My writing group will read and help me launch Clockwork at Cordia Senior Living, Traverse City

Oct 25 7:00 Antrim County launch of Clockwork, Bee Well Cidery, Bellaire, MI.